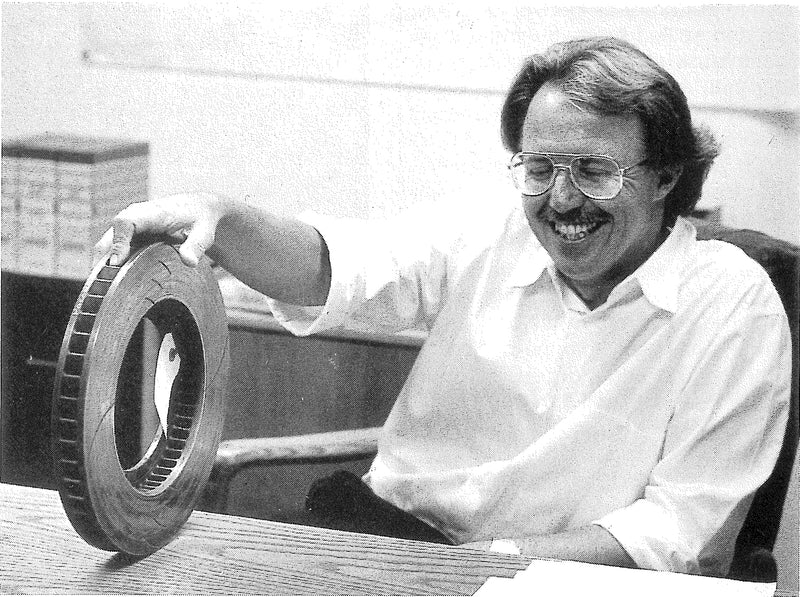

Bill Wood is always smiling. Why not? He's happy doing what he's doing, and he's made it to number one after starting with nothing. (Dick Berggren photo)

Bill Wood of Wilwood Engineering

It's a good thing Bill Wood never went to business school. They'd have told him it wasn't possible to build a business like Wilwood Engineering the way he went about it.

Growing Up

As a kid, Bill Wood didn't really fit in. "Quite frankly," he admits, "I was a discipline problem." Bored with high school, he did well only in math, science, and cutting class. "I didn't come out of high school with a real impressive grade point average," he explains. "I think it was about a 1.5." As a pre-teen, the always smiling Wood did things that showed he was smarter than his school grades indicated. At a very young age, he not only liked engineering, he had an aptitude for it. He had made a youthful career of taking things apart to see how they worked. Sometimes, he put them back together. A favorite was to tinker with cars. He remembers a dune buggy project in which "we took a '54 Chrysler and made it about five feet long."

Yet, despite his interest in and talent in engineering, college was out of the question. He couldn't get in because of his awful high school grades. After high school graduation, an event Wood considers to have been the result of the school wanting to be rid of him, and good luck, he took a job with a relative as an apprentice toolmaker. "I did that for about a year, working 58 hours a week. When I was 18, I came to believe that there had to be more than that to life." Looking for utopia, Wood packed his knapsack and moved to Yosemite National Park, where he was happy washing dishes and taking in nature.

But, the Yosemite experience was brief. Like many kids with bad high school grades and no education beyond, Wood was drafted into the military. While there, he got lucky. The Army taught him machining. He did so well at it that soon he was teaching others the trade. When he was discharged, with the help of the G.I. Bill, he enrolled in Pierce College in California's San Fernando Valley with the intent of doing something completely different.

"I got a degree in political science. When I got out of the Army, I was kind of annoyed. The antiwar thing and that kind of stuff, so I decided to go into politics and change the world," Wood remembers.

Like most of what Bill Wood has set out to do in his life, college included a mixture of the required with some fun. He took engineering courses, which were fun, with the required political science courses and wound up with his political science degree and only fifteen credits short of an engineering diploma. It took seven years for him to earn a four-year degree.

The career track of nearly flunking out of high school, going to Yosemite, and a commune with nature followed by the military and a seven-year undergraduate degree wasn't the kind of route that a local guidance counselor might recommend for someone destined to become an industrial powerhouse. But, there are no real maps for such things, and even if there were, Wood wouldn't have known how to read them because he didn't know where he was going.

While a student, Wood paid his bills by doing engineering. But, he was a better engineer than businessman. "A company that owed me a bunch of money suddenly decided they weren't going to pay me. I wasn't really sophisticated in the ways of the business world and got stuck for, what for me at the time, was a considerable sum of money. I wound up broke."

So, Wood did the honorable thing.

He got a job.

Hurst-Airheart Brakes

After hearing they were looking for engineering talent, Wood presented himself at the employment office of Hurst-Airheart. He was hired on the spot, but the company was a mess. It had just been purchased by Sunbeam, and Wood remembers, “We were a division of a division of a division. Management was terrible. I mean, it was awful." After the company president quit, it took nine months to find another, and during the interim, nobody was officially in charge.

"What actually happened was that I wound up basically running the company because the sales manager was gone all the time. The chief engineer, my actual boss, was the son of the guy who founded Airheart, and he was there, but he didn't want the responsibility. So, I had nothing to lose. We just did it the way I wanted to do it. I literally ran the company."

At 26 years old, Wood found himself getting terrific and cost-free training for running his own company later. During the learning period, the mistakes he made were at someone else's expense. Eventually, Airheart became organized and hired a new president, a tough-guy fresh from the Marines. Wood recalls, "A couple of weeks after the new president started, he decided I was not really a team player. Told me if I didn't get my act together, he was going to, and these are his exact words, 'break my spirit."'

At the time, Wood was working on Hurst's brake line, which was about all there was for stock car racing. Hurst-Airheart calipers and rotors had a near 100% market share, the kind of thing any company executive dreams of having. And, although Wood had ideas about how to improve the product, there was so much else going on at the company, nobody much wanted to listen.

Starting Again From Zero

Unwilling to submit to the new company president breaking his spirit, the now freshly unemployed Bill Wood contacted Frank Deiny, a racer who owned California's Speedway Engineering, and who was trying to make his own brakes. "So, I went over there and started helping him finish up his brakes. He was buried in a lot of other stuff, and it ended up that he and I worked out a deal. I took what tooling he had and finished it up on my own, and I sold him the brakes, which he couldn't get from Airheart." And that was the beginning of Wilwood engineering.

Wood had no backers, no investment capital, and he had no money in the bank. What he did have was a willingness to work hard and risk everything. In the beginning, there wasn't much to risk because Wood didn't have much.

At first, he survived by fast footwork and unemployment insurance, both of which he preferred to debt. He did engineering work on the kitchen table in his apartment using a T square. Because he'd done engineering for several area machine shops, he knew their owners and was able to talk them into letting him use their machines at night to make his calipers. This was as low buck a start-up as ever was. Even his kitchen appliances became test equipment. At one point, Wood used his oven to test brake calipers at temperature and spilled brake fluid into it. "I couldn't use my oven for a long time after that," he remembers. "Anything I cooked in it tasted like brake fluid."

Bill Wood's mind is on the numbers of business. Has been right from the time as a student he didn't get paid for his engineering work. Behind his desk today is a chart that tracks the company's revenues from the beginning. The books are in his desk's top drawer. They start from the beginning with the first entry dated October 21, 1977, a sale of $3,048 to Frank Deiny.

The books also show that Bill Wood had earned a profit of $398.08 in his first month in business. He's doing a bit better now. As the company grew, Wood poured its profit back into Wilwood. He started his own machine shop, which began in leased space in the corner of someone else's motorcycle sidecar factory. Wood taped off a small area, put in a workbench, tapped a line off the sidecar factory's air compressor, and he had his first production facility at $50 a month rent. His current shop is a bit bigger at 27,000 square feet. It's not big enough.

When the business started, he had no idea of how far he'd go. "I remember one time thinking I could probably [gross] $250,000 a year. I remember that being a target." Current sales figures are a closely guarded secret, but it's likely that they are ten to twenty times greater than Wood's initial goal.

Learning the Track

Wood knew the market for racing brakes was big, but he didn't know where it was. To find out, he subscribed to Stock Car Racing magazine and National Speed Sport News. "I started by calling places that advertised, anything having to do with race cars, and telling them I had brakes. I made up a little advertising brochure with pictures and mailed it out. I'd get up at 5 in the morning, California time, so I could call East and get the night phone rate."

Wood's pitch was simple.

"I told them we had a better product." And he did. At least he did when he could get his hands on the brakes he designed.

With no money to pay for them, Wood ordered castings and picked them up when he had orders for finished brake sets. Machining was performed quickly so he could turn the rough castings into salable pieces. With the money that came in, he paid his casting bill and ordered more. The whole thing was a fast shuffle of getting an order, getting pieces, machining them, getting paid, and then paying for the original rough castings.

An order from Tiger Tom Pistone, a sometime stock car driver, full-time character, and speed shop operator deep in the heart of Southern stock car country, really got things going. Pistone had heard about Wood's brakes, knew there had to be something better than the Hurst pieces, and Tiger Tom handed over a check for $5,000 for an order. It was the biggest order Wood had gotten. That order was quickly followed a similar buy from Sonny Koszella (Koszella Speed in Rhode Island) and "a guy named Maynard Troyer that I'd never heard of." Those 1977 orders provided the working capital that was the foundation of Wilwood Brakes, now the largest manufacturer of racing brakes in the world.

Wood admits that "My timing was good." Short track racers trying to get away from the old Buick drum brakes that had been the standard and who had tried the Airheart calipers knew there had to be something better. The Buicks suffered from all the liabilities of drum brakes, including fade, high cost, and a lack of reliability. The Airhearts were so bad, their fluid leaked onto the garage floor as the race car sat still, forming four puddles, one under each caliper. They couldn't even sit still without failure, so Wood didn't have to reinvent brakes to create an improvement.

A Fortuitous Meeting

Yet, despite his interest in fast cars, Bill Wood knew very little about auto racing. He knew about race cars, but he sure didn't know about the business of making a product to meet a demand.

Koszella and Troyer had been around a long time, and they knew the market. They persuaded Wilwood to make an ultralight caliper with a large piston and a bigger pad. Racers quickly began buying the new Wilwood brakes from Pistone, Koszella, and Troyer.

But there was more good fortune to come. "I had moved into a shop in Chatsworth and was sitting at my desk one night. It was about six o'clock, and this guy walked in, introduced himself as Richie Evans, and wanted to know if he could work out some sort of deal for brakes.

"I figured, wow, I knew who Richie Evans was, but I had never talked to him. He hadn't called. Said he was out this way, someone told him Chatsworth was nearby, and he walked in the door. After that, we worked with Richie, and every car Richie built after that had our brakes in it. I listened to him.

"Richie was the best guy in the world. He was loyal. If there was a problem, he told you and nobody else. But, if he liked what you had, he told everybody. Plus, if he ran it, everybody else ran it too. He won everywhere he went. He made us."

As a for-instance of what Richie Evans did for him, Wood tells the story of the bubble hub he invented. It was a hollow wide-five hub that was both lighter and stronger than the solid hubs everyone else made. It looked so different, when most racers first saw it, they figured the hub would break. Not Richie Evans.

The first time the hub was run was on Evans' car at Martinsville in a modified race that produced an incredible slam-bang finish that made news everywhere. The race came down to a classic Richie Evans-Geoff Bodine confrontation, and when the white flag neared with both cars evenly matched and side-by-side, Wood remembers, "You knew they were going to wreck each other. It was only a question as to whether one would make it to the checkered flag."

They banged coming down for the white. Bodine took his shots, Evans took his, and when they came off the fourth turn with the checkered waving, the back end of Bodine's car swung, Evans went into the wall, his foot still on the floor. Bodine began spinning, and the two cars hit each other, the wall, then hit each other again with parts flying through the air. Evans’ car was virtually destroyed, and Bodine’s looked no better. A classic Evans’ victory lane shot shows the bent wreckage of his car behind him as Evans, with a cat like grin, was holding the checkered flag. The new bubble hubs, all four of them on the car that day, held up.

That race with its crashing win put Bill Wood's new hollow hub at the top of every driver's wish list. If Richie Evans couldn't break the hubs against Martinsville's concrete wall and Geoff Bodine's race car, well, maybe they couldn't be broken at all.

Risks and Rewards

Drawing and building the hubs, like starting the business in the first place, was a risky move. Wood didn't put up someone else's money, he put up his own. If things didn't work out, Bill Wood's own wallet suffered. He never went to a bank and borrowed money, never sold stock or subjected someone else's money to the risk of his ideas. It was always his own ideas, his own risk.

It's a good thing Bill Wood never went to Harvard Business School. They'd have told him that's not a good way to do business.

The suit-and-tie guys wouldn't have liked the way Bill Wood turned racers on to racing brake fluid, either. When Wood got into it, there was only one company marketing small containers of brake fluid to racers, and the product was expensive. It was well known that not all brake fluid was created equal and that brake fluid should be kept in small, tightly stoppered containers. The stuffs hygroscopic, meaning it sucks water out of the air, and when it soaks up water, brake fluid boils as easily as, well, water. Wood figured better fluid in small containers was a good racing product.

"We found a company that made really good brake fluid," says Wood. The only hitch was, Bill Wood had to buy a lot of the stuff. How much?

A tank car."

When the deal was done, Bill Wood's bank account was empty again, but he had quite a lot of brake fluid. He had, in fact, around 2,000 cases of brake fluid, with 24 cans in each, hogging up much of his shop. Wood didn't know if he could sell brake fluid, he'd just stuck his neck and his wallet out again. But, it turned out he could sell the stuff and that one tank car buy turned into many more. Now he's America's leading marketer of racing brake fluid.

HOW TO MAKE IT IN RACING

Did you ever want to earn your living in racing? Take the advice of a man who at a young age is the dominant player in his field, a man able to get filthy rich simply by putting a for sale sign in front of his business.“If I was looking to get involved in racing from a manufacturing point, the thing to do is look for a niche. Look for something that is not being done well, and there's always something.”"You can't go out there and do what everybody else is doing. Especially against an established company. I went against an established company, but they had been sold and sold to where they didn’t have any management.” Jumping into a market where there is a good, strong, dynamic company may not be the best bet.“Look for something that's not getting done as well as it might. If it turns out that you also find a poorly managed company, that's a definition of opportunity."Wood stresses the importance of closely watching the company’s money. “We do it fairly simply," he says, "We have a bookkeeper, and our books are computerized. I was involved in setting up the computer system. And, I started keeping the books. It doesn't take my time now. At the end of every month, they hand me a financial statement that tells me how we are doing. I know what areas we are making money at and which we are not. I keep an eye on that. You have to.”"I don't like doing that. I do it because I have to. I've never been able to hand it over entirely to someone because it's my money."-Dick Berggren

Always Expanding

Seven years ago, Bill Wood began bringing his machining in-house. The business was going well, so it seemed that the time was right to rely less on others and more on his own ability to make things. Now, virtually all of the machine work done on Wilwood brakes is done in the company's own huge shop in California, a shop whose machines are run by computers. The shop’s owner says with pride that his factory produces the best racing brakes in the world.

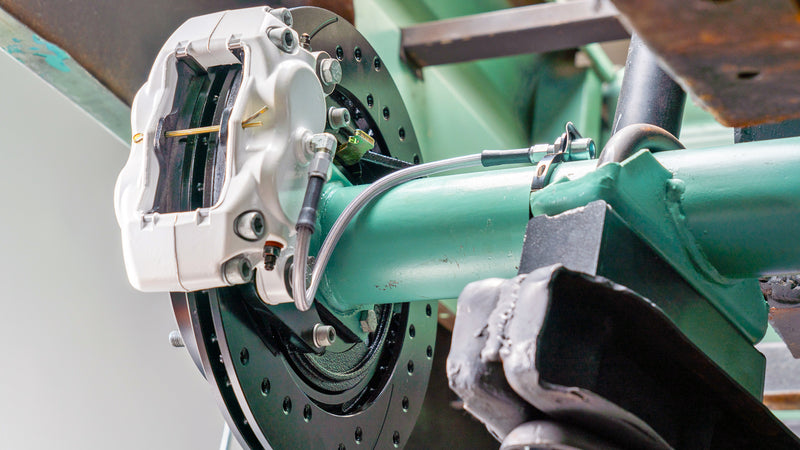

To develop the best brakes, two years ago, in characteristic fashion, Wood installed a brake dyno. Most brake dynos are devices in which a brake rotor can be attached to a shaft turned by a hundred horsepower electric motor. A fixed caliper then squeezes the rotor to test both. That's just fine for testing almost any kind of brake.

But, guys with dynos like that don't worry about slowing a behemoth 3500 pound Winston Cup car at the end of Martinsville, Virginia's long straightaways some 1,000 times during the course of an afternoon race. So, Wood built a dyno that seemed appropriate for the job (see lead image). It's powered by a small block Chevy, and it turns a rotor hard enough and fast enough to not only test the limits of brake calipers, it can heat a rotor enough to melt it! "We're able to test the extremes of the envelope," Wood says.

Bill Wood's story of making it in racing is a story of unusual success, even for this Stock Car Racing Magazine series. At age 44, Wood could easily sell Wilwood for millions of dollars and retire to a life of leisure. But that's about as likely as expecting Dale Earnhardt to quit racing because he's grown tired of it

"I think I'm one of the luckiest people in the world," Wood explains. "I'm having fun. I like doing this. I really, really enjoy what I'm doing. The racing industry, in general, has a lot of people like that. Most of the people in it are people who, like me, enjoy racing."

In fact, if anything, rather than selling out, Bill Wood is turning up the intensity. He's looking at other markets like snowmobiles and motorcycles for his genius. And, he wants to get into areas of racing that have been, until now, closed to him as he invested every dime he earned back into his company.

"I'm now making some real high-end stuff and some high-quality intermediate stuff. We are making brakes for F-1, Indy cars, Formula 3000," and international racing. The primary reason for these projects isn't the bottom line. Says Wood, "At $2,000 per caliper [for Indy car brakes], you lose money." But, even though he expects to lose money at it, Wood is determined to dominate the Indy car brake field. If the cars are foreign, he figures, at least their brakes will be American. He likes the idea of Americans taking the lead and intends to do some lead-taking himself. Important to Saturday night racers is that the results of research into racing's top leagues filter down to everything Wilwood makes.

If only some of Wood's current dreams become reality, and this guy's got a long track record for turning dreams into reality, America will soon dominate the ultra-high performance brake field everywhere. For those who are looking to American companies to restore some of this country's pride, Bill Wood and what he's doing now may prove to be a model. He intends to dominate the worldwide racing brake marketplace.

Another Fortuitous Meeting

Bill Wood has made it in racing because of his unusually effective mechanical mind, his willingness to take extraordinary risks, and because he found some terrific racers along the way who helped him as he helped them. His office walls have photos of some of those racers, one of them Richard Petty. It's an old photo, that shot of Wood and Petty and both of them have longer than currently-fashionable hair and very long sideburns. The picture was taken at Riverside. Wood talked his way in to see Petty that day. We'll let him tell the story.

"I had no credential, so I went to the gate and gave them my business card. Asked to see Bill Gazaway [at the time, NASCAR's competition director]. The guy came back about ten minutes later and brought me to the driver's lounge. Gazaway was in there, and I got introduced to him. He was kind of a gruff guy. I handed him one of my calipers, told him I was making brakes for the cars, and I wanted to get into the garage and show them to the drivers. I swear to God, he looked at me and said, 'Why don't you talk to Richard over there. He knows a lot about brakes.' So I turned around, there is a guy standing there, and I didn't recognize him. He had just grown a beard. So, I said, 'Richard who?’

"Darrell Waltrip was sitting across from me, and he falls on the floor. I mean, he was rolling on the floor. Gazaway said, 'Richard Petty. You've heard of him, haven't you?' And I turned purple.

"Richard doesn't blink an eye. He walks up, takes a caliper, and looks at it, took me over to his race car, and he sat there and talked to me for two hours. We just talked about brakes, what he had done, what I had done, and he said he'd try some of the brakes.

"I gave him a set, but he's bought them from me ever since."

There are other pictures on the walls at Wilwood, pictures of sprint car driver Doug Wolfgang, stock car driver Ron Hornaday, and others. There's a story to go with every picture.

Bill Wood has made it in racing. The racers in the pictures, not bankers or investors, are the only people who lent him a hand getting there.

Reprinted from - Stock Car Racing March 1993 by Dick Berggren

Will,

Thank you for your long time use of our brakes, and best of luck with your new car. You can find contact information for Spike and the entire motorsports support team on the home page of our racing products here – https://www.wilwood.com/Racing/Index.

Have used your product for probably 35 years. Was looking for information on recommendations for UMP modified. In the process of buying a new car. Lethal from David Streme. We have been running the modified since 1997 . Now my daughter drives.Have always bought used cars.l have always talked to Spike before but has lost his number Thank You for any information and part numbers I could get. Will Rowe